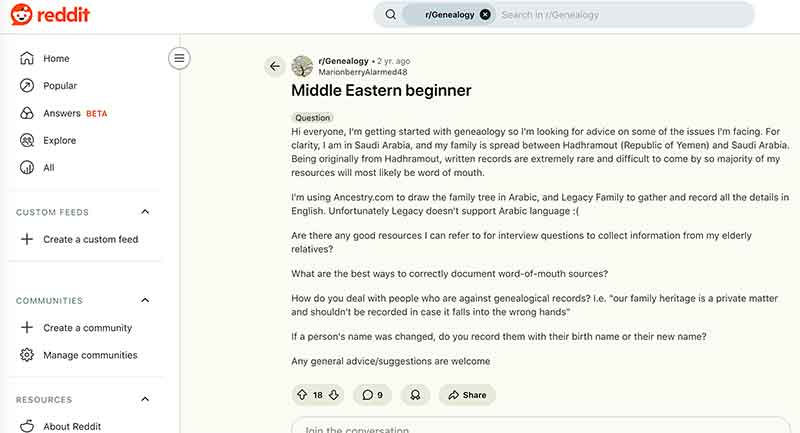

Jose Mier, from Sun Valley, CA, asks the question, “what are the pitfalls of doing Middle Eastern generalogical research?” Some answers can be found on sites like Reddit. Others may take much more effort.

Genealogical research is an exciting and deeply personal endeavor, connecting individuals with their ancestry and heritage through documents, oral traditions, and historical records. However, conducting genealogical research in the Middle East presents a unique set of challenges. The region’s complex history, rich cultural and religious diversity, periods of conflict, and inconsistent archival practices make tracing family histories particularly difficult. Despite these challenges, there are resources and strategies that can help researchers make progress.

This article explores the main problems encountered when doing genealogy in the Middle East and highlights several tools, organizations, and archives that can provide assistance.

I. Challenges in Middle Eastern Genealogical Research

1. Lack of Centralized Civil Registration

One of the primary challenges in Middle Eastern genealogy is the absence or late development of centralized civil registration systems. Many Middle Eastern countries did not begin systematically recording births, deaths, and marriages until the late 19th or early 20th centuries—much later than many European nations. Even where these systems exist today, early records may be incomplete, inconsistently maintained, or inaccessible to the public.

In some areas, vital events were traditionally recorded by religious institutions rather than state agencies. This means that birth, marriage, and death records may be housed in mosques, churches, or synagogues, and access to them depends heavily on local religious leadership, community ties, or political conditions.

2. Political Instability and Armed Conflict

The Middle East has experienced extensive conflict and regime change over the past century, from colonial rule and wars of independence to modern civil wars and international interventions. Countries such as Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Libya have seen significant destruction of infrastructure—including archives and historical records. Political upheaval can lead to the loss, relocation, or deliberate destruction of genealogical documents.

For example, war in Iraq and Syria has damaged numerous libraries and government offices, erasing decades or even centuries of documentation. Likewise, conflicts in Lebanon, the Palestinian territories, and Afghanistan have made access to civil records either impossible or extremely risky.

3. Limited Access to Archives

Even when records exist, researchers may find them difficult to access. In many Middle Eastern countries, government archives are not digitized, and physical access may be restricted to authorized personnel or local citizens. Researchers from abroad often face bureaucratic barriers, language limitations, or security concerns.

Some governments are wary of providing access to genealogical records due to privacy concerns or political sensitivities. For instance, access to Ottoman-era records may be restricted in Turkey, and many Israeli archives related to early immigration are limited or highly regulated.

4. Language and Script Barriers

Genealogical research in the Middle East often requires fluency in multiple languages and scripts. Arabic is the dominant language in many countries, but Turkish, Persian (Farsi), Hebrew, Armenian, Kurdish, and various dialects are also common. Ottoman Turkish—used in official records of the Ottoman Empire—features a unique script that requires specialized training to interpret.

Even for researchers familiar with modern Arabic or Persian, old handwriting styles, regional terminology, and pre-modern vocabulary can create major obstacles.

5. Oral Tradition vs. Written Records

In many Middle Eastern societies, especially in rural or tribal communities, family histories are passed down orally rather than documented in writing. These oral genealogies are often rich in detail but may lack exact dates or standard naming conventions. Tribal affiliations, honorifics, or religious titles might be emphasized over formal recordkeeping.

While oral tradition is invaluable for understanding heritage, it can also introduce inconsistencies, embellishments, or omissions, especially as stories are transmitted across generations.

6. Name Variations and Patronymics

Name structures in the Middle East differ significantly from Western conventions. Many people carry multiple names that reflect their father’s name, grandfather’s name, place of origin, or profession. For example, someone might be known as Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Youssef (Ahmad, son of Muhammad, son of Youssef), but only part of this name may appear in official records.

Additionally, spelling variations due to transliteration—especially from Arabic to Latin script—can make it hard to trace individuals across documents. For example, the name “Abdul Rahman” might appear as “Abdurrahman,” “Abd al-Rahman,” or “Abd ar-Rahman,” depending on the language and transcription system used.

7. Religious and Sectarian Sensitivities

The Middle East is home to a mosaic of religious communities, including Muslims (Sunni, Shia, Alawi, Druze), Christians (Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant), Jews, Baha’is, and others. Religious identity plays a significant role in how records are kept and who has access to them.

In some cases, religious minorities have preserved their own records—such as Armenian Apostolic churches or Jewish community archives—but gaining access may require proof of ancestry, personal connections, or clergy approval. Sectarian tensions may also affect the availability or integrity of records.

II. Helpful Resources for Middle Eastern Genealogy

Despite the many obstacles, there are growing resources and strategies available to genealogists researching Middle Eastern ancestry.

1. Ottoman Archives (Turkey)

The Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi (Prime Ministry Ottoman Archives), located in Istanbul, contains millions of documents from the Ottoman Empire, which ruled much of the Middle East for centuries. These archives are rich in tax records, population registers (nüfus defterleri), and military service documents.

While many of these records are written in Ottoman Turkish and not yet digitized, scholars and some genealogy groups offer translation and research services. Researchers may need to apply in advance for permission and may require local support.

2. Israel State Archives and JewishGen

For those tracing Jewish ancestry in the Middle East (including Iraq, Iran, Yemen, and Syria), JewishGen.org provides databases, community pages, and links to synagogue and cemetery records. The Israel State Archives and Central Zionist Archives also contain immigration documents, censuses, and civil registrations from British Mandate Palestine and the early state of Israel.

3. FamilySearch.org

Operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, FamilySearch has digitized millions of records worldwide, including church registers, civil documents, and censuses from some Middle Eastern countries. While coverage is limited compared to Western Europe or North America, it’s an excellent starting point.

FamilySearch also offers a catalog of microfilmed records held in Salt Lake City, which can sometimes be requested or viewed online.

4. Ancestry.com and MyHeritage

Though primarily focused on Western records, both platforms offer user-submitted family trees and limited Middle Eastern data collections. MyHeritage, headquartered in Israel, includes some Jewish and Israeli records. Both services offer DNA testing, which can be especially useful when documentary evidence is lacking.

5. Local Religious Institutions

Many genealogists working in the Middle East find their best leads through religious institutions. Churches, synagogues, and mosques often have baptism, marriage, and burial records not available elsewhere. Contacting these institutions requires persistence and may benefit from involving local intermediaries.

For Christian ancestry, the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem, Maronite Patriarchate, and Greek Orthodox Church have long-standing archives. Jewish genealogists may consult Beit Hatfutsot (The Museum of the Jewish People) for family trees and community histories.

6. Embassies and Cultural Organizations

Some researchers have found success by working with embassies, cultural centers, or diaspora organizations that maintain connections with communities in the Middle East. These groups sometimes sponsor heritage preservation projects, oral history initiatives, or facilitate contact with record holders.

Examples include:

- American Lebanese Historical Society

- Assyrian Universal Alliance

- Iraqi Jewish Archives Project (managed by the U.S. National Archives)

7. Academic and Regional Historians

University historians, anthropologists, or Middle East studies departments often conduct fieldwork and archival research in the region. Many publish studies or curate databases that may include genealogical data or population surveys. Reaching out to these scholars can yield surprising results and provide much-needed context for family histories.

III. Strategies for Success

Despite the barriers, persistence, flexibility, and creativity are key to successful genealogical research in the Middle East. Here are some final tips:

- Start with Home Sources: Interview family members, collect photos, religious certificates, passports, and letters.

- Document Oral Histories: Preserve family stories, even if unverified. These can provide clues to names, places, or migrations.

- Understand Historical Borders: Modern national boundaries may not align with ancestral homelands—research the empires and administrative divisions in place at the time.

- Work with Translators: Language specialists and paleographers (for old scripts) can be invaluable.

- Network with Diaspora Groups: Connect with others from the same village, tribe, or religious group. Shared information can open new avenues.

- Use DNA Testing: When records are unavailable, genetic genealogy can reveal connections to relatives or ethnic origins.

- Be Patient and Respectful: Access to archives may take time, and some communities may be protective of their heritage. Always approach with respect.

Conclusion

Genealogical research in the Middle East is not for the faint of heart. The challenges—missing records, political barriers, language issues, and religious sensitivities—are real and often formidable. Yet, for those determined to uncover their family roots, the journey can be incredibly rewarding.

While traditional archives may be limited, the rise of digital platforms, diaspora networks, DNA tools, and cultural institutions offer new opportunities to piece together the past. With careful planning, patience, and cultural awareness, even the most challenging family histories in the Middle East can come to light—one name, one document, one story at a time.