Jose Mier, Sun Valley’s amateur genealogist, explores the subject of food and genealogy. After all, as families we sit down with different generations to eat. We may also hand down family recipes, etc. There is a wealth of information out there on this subject including the Indiana State Library blog.

Food has long served as more than mere sustenance; it acts as a cultural artifact, a vessel of tradition, and a deeply personal connector to one’s roots. In the field of genealogy, food can be a surprisingly rich and evocative tool for uncovering and preserving family history. When we trace our ancestry, we often look to birth records, census data, and photographs. But recipes, cooking techniques, and the cultural rituals surrounding meals offer a vivid, sensory dimension to the past that documents alone cannot provide.

One of the most direct ways food enters into family history research is through heirloom recipes. Handwritten cards, stained with generations of use, are often treasured keepsakes passed down from grandparents or great-grandparents. These recipes are more than instructions; they are living history. A family’s version of pierogi, gumbo, tamales, or Sunday roast tells a story about the geographic origins of ancestors, their adaptations to new environments, and the values they held. Sometimes the recipes include substitutions or annotations that reflect times of scarcity or changes in available ingredients—clues to economic conditions or migration patterns.

Cooking traditions can also act as a portal to ancestral lifestyles and environments. For instance, discovering that your ancestors used a root cellar, fermented their own vegetables, or relied heavily on foraged foods like wild greens and mushrooms can tell you much about their daily lives and survival strategies. These practices may also offer insight into the local ecology of their homeland and their relationship with nature. Understanding these culinary habits can help researchers build a more holistic picture of their ancestors’ lives.

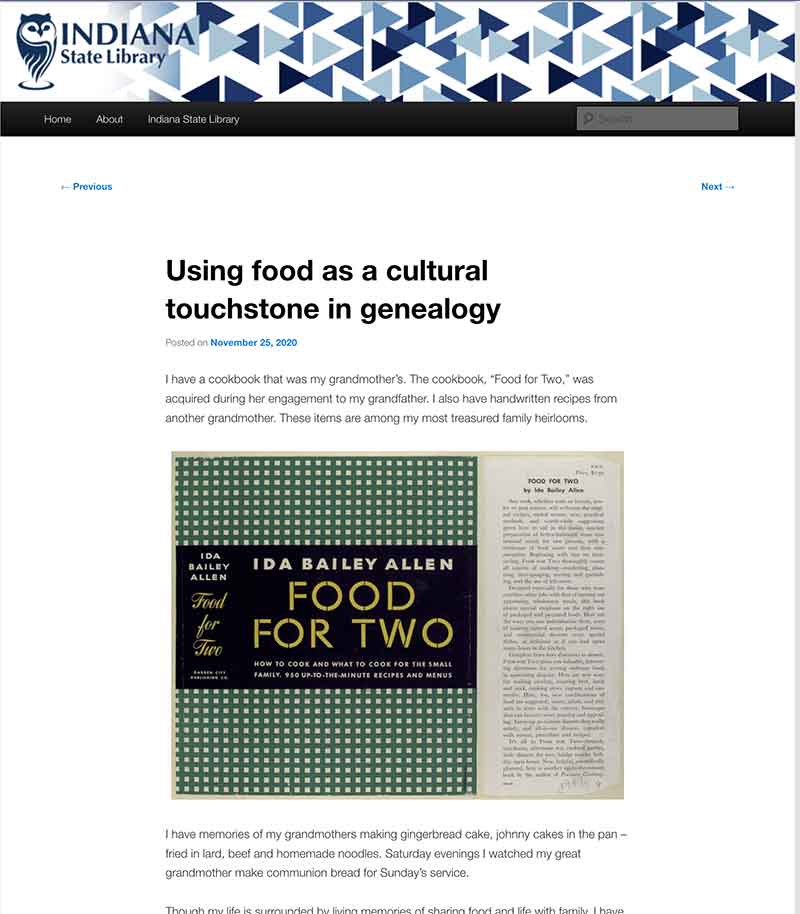

Food-related artifacts, such as family cookbooks, kitchen tools, or utensils, also serve as tangible connections to the past. These items, often passed down through generations, carry sentimental and historical value. A cast-iron skillet used by a great-grandmother might have prepared hundreds of meals, its well-worn surface etched with the history of family gatherings and traditions. Similarly, traditional cookware like a molcajete, samovar, or tagine can indicate specific cultural origins and culinary customs.

Oral histories surrounding food can be a rich source of genealogical information. Interviews with older relatives frequently yield stories about how meals were prepared, what foods were reserved for holidays, and how certain dishes became associated with family milestones like weddings, funerals, or baptisms. These stories often include details about family members, their roles, and the emotional connections tied to food. As memory tends to be more vivid when linked to sensory experiences, food often acts as a powerful catalyst for recollection.

Food can also be used as a tool for reconnecting with lost or fragmented parts of a family tree. For adoptees or those with incomplete lineage records, identifying cultural or regional food preferences may help uncover potential ancestral links. Culinary DNA, a concept gaining traction, refers to the inherited palate or preferences that align with one’s ethnic background. While not a substitute for traditional genealogical research, food can provide leads or at least offer meaningful engagement with one’s suspected heritage.

Digital genealogy platforms and family history blogs increasingly incorporate food as a narrative device. Sharing family recipes online, along with the stories behind them, not only preserves these traditions but also invites collaboration from extended relatives who may contribute additional details or variations. These exchanges often lead to discoveries that documents alone could not yield, such as the migration routes of certain dishes or the evolution of a recipe as it moved across continents.

Religious and ceremonial foods offer another window into ancestral life. Many religious traditions involve specific dishes prepared and consumed in ritualistic contexts, such as challah for Shabbat, koliva for Eastern Orthodox memorial services, or mooncakes for the Mid-Autumn Festival. These foods are imbued with symbolic meaning and often follow strict preparation guidelines that have remained unchanged for centuries. Studying the role of such foods within a family can reveal much about spiritual beliefs, community affiliations, and the seasonal rhythms that shaped ancestral lives.

Seasonal and agricultural calendars also influence family food traditions. Examining when and how foods were prepared and preserved—such as summer canning, fall butchering, or winter baking—can shed light on agricultural cycles and labor patterns. These insights often correlate with historical events, such as the introduction of refrigeration, the industrialization of food production, or wartime rationing. Understanding these changes provides a broader context for interpreting a family’s shifting culinary practices.

Migration and immigration stories are frequently told through food. When families move from one country to another, they often bring their food traditions with them, adapting them to new ingredients and tastes. This culinary adaptation becomes a record of the immigrant experience. For instance, Italian-American families might incorporate locally available produce into traditional recipes, creating a unique regional variation of a dish. Tracking these changes can reveal where and when a family settled, how they interacted with their new community, and how much of their heritage they retained or modified.

Genealogical research can also benefit from exploring local food customs and regional specialties of ancestral homelands. Visiting the areas where one’s ancestors lived and sampling traditional dishes or visiting local food markets can provide immersive context. These experiences often trigger emotional connections and deepen one’s appreciation for the daily lives of ancestors. Moreover, regional food histories are frequently well-documented, providing supplementary information for family historians.

In some cases, food even intersects with occupation and economic status. Knowing that an ancestor was a baker, butcher, or brewer offers clues to their social standing, daily routine, and community role. Occupational records combined with food traditions can paint a detailed portrait of a person’s life and values. For example, a family with generations of fishermen may have a culinary tradition centered on seafood, with specific recipes passed down that reflect not only diet but also maritime culture and knowledge.

Food also plays a role in the emotional landscape of family history. Many people associate certain dishes with comfort, love, or loss. The act of preparing or sharing a family recipe can be an emotional tribute to a deceased loved one, a way of keeping their memory alive. These emotional connections provide a compelling reason to preserve culinary heritage alongside names and dates in a family tree.

Even genetic genealogy can intersect with food. Advances in DNA testing often reveal ethnic backgrounds that prompt culinary exploration. Someone discovering they have Scandinavian ancestry may experiment with dishes like gravlax or Swedish meatballs, finding a tangible and enjoyable way to connect with newly uncovered roots. While this kind of culinary engagement is more symbolic than evidential, it adds a personal and emotional dimension to the often-technical process of DNA analysis.

Food festivals and cultural events offer additional opportunities for genealogical exploration. Attending an Irish festival, Greek Orthodox Easter celebration, or Chinese New Year event often includes exposure to traditional foods and rituals. These experiences can spark curiosity about one’s own heritage and provide a gateway to more formal genealogical research.

In an increasingly globalized and digitized world, where family members may live continents apart, food offers a unique means of connection. Cooking a family recipe can bridge generational and geographical divides, creating a shared experience even when physical presence is not possible. For families committed to preserving their heritage, organizing recipe collections, creating digital cookbooks, or hosting intergenerational cooking sessions can become cherished traditions that reinforce family identity.

To integrate food into your family history research, start by collecting family recipes and recording the stories behind them. Interview older relatives about food memories, special meals, and traditional preparations. Photograph heirloom kitchen tools and document their origins. Explore regional food histories connected to your family’s homeland. Visit cultural festivals and sample traditional dishes. Consider creating a family cookbook or blog that not only preserves recipes but also captures the stories, emotions, and histories behind them.

In conclusion, food offers a flavorful, emotional, and deeply cultural dimension to genealogy. It transforms research from a collection of facts into a lived, shared experience. Whether through a recipe lovingly handed down or a dish rediscovered through DNA results, food connects the past to the present in a way that few other elements of family history can. As you trace your lineage, don’t overlook the power of what’s on your plate—it just might lead you to who you are.