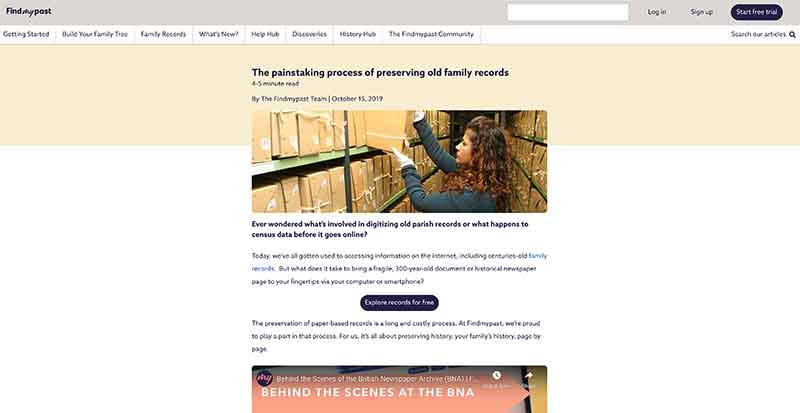

Jose Mier, Sun Valley genelogy enthusiast, looked into techniques on how old (sometimes centuries-old) documents are being preserved and digitized for later generations. One example can be found on FindMyPast.com.

Preserving old historical records—such as birth and death certificates, baptismal registers, marriage licenses, wills, and other vital documents—is one of the most important undertakings in maintaining the continuity of human history. These records form the backbone of genealogical research, historical scholarship, and cultural memory. Yet, many of these precious materials were created on fragile media—paper, parchment, or ink formulations—that were never intended to survive centuries of handling, environmental stress, and neglect. The methods used today to preserve them represent a blend of science, art, and dedication. In the following 1,500 words, we’ll explore in detail the steps archivists, conservators, and historians take to protect these irreplaceable documents, from physical stabilization and environmental control to digitization and long-term storage planning.

Understanding the Nature of Historical Records

Before any preservation work can begin, archivists must understand the materials they’re working with. Historical records vary greatly in composition. Some may be handwritten in iron gall ink on cotton rag paper, while others might be printed on wood-pulp paper that becomes brittle over time. Parchment, made from treated animal skin, is extremely durable but sensitive to humidity. The inks, pigments, and adhesives used in older documents can react differently to light and air exposure.

Each material has its vulnerabilities. Paper, for instance, deteriorates as cellulose fibers break down, a process accelerated by acids present in the paper or introduced from the environment. Ink can fade, feather, or even corrode the paper it sits on. Knowing these characteristics allows conservators to design appropriate storage and treatment plans that protect each document type effectively.

The First Step: Assessment and Cleaning

When historical records are first acquired by an archive or library, they undergo a thorough assessment. This process determines their condition, identifies signs of damage, and helps prioritize preservation actions. Common issues include tears, brittleness, mold, insect damage, water stains, and ink corrosion.

Dry surface cleaning is often the first treatment step. Using soft brushes, vinyl erasers, or specialized sponges, conservators gently remove dust, dirt, and surface grime that can contribute to degradation. The goal is to clean without damaging fragile materials. In some cases, pages stuck together by moisture or mold must be carefully separated under controlled conditions to prevent loss of text.

If mold or mildew is present, the document is isolated and treated with appropriate antifungal methods. Mold not only weakens paper but also poses health risks to handlers. For this reason, cleaning and stabilization often take place in conservation laboratories equipped with filtration systems and protective gear.

Stabilization and Repair

Once cleaned, damaged documents often require stabilization to prevent further deterioration. Small tears are mended using thin, acid-free Japanese tissue and wheat starch paste—a reversible adhesive favored by conservators because it does not harm the original paper. Larger areas of loss may be supported with archival-quality repair paper. The emphasis in conservation is always on minimal intervention: preserving as much of the original material as possible while ensuring structural integrity.

For documents that are particularly brittle, encapsulation in Mylar (a transparent polyester film) can protect them from handling while keeping them visible for study. Encapsulation differs from lamination—an outdated process that involved sealing documents between plastic sheets using heat or adhesives, which often caused more harm than good. Modern encapsulation uses static adhesion and allows for future removal.

In some cases, deacidification is necessary. This process neutralizes acids in paper using an alkaline solution or vapor treatment. Deacidification can greatly extend the life of acidic paper, such as newsprint or low-quality 19th- and 20th-century documents. However, it must be done cautiously to avoid altering inks or dyes.

Environmental Control: The Heart of Preservation

The environment in which historical documents are stored is perhaps the single most important factor in their preservation. Fluctuations in temperature and humidity are especially damaging because they cause paper and ink to expand and contract, leading to warping, cracking, or ink flaking. High humidity encourages mold growth and insect activity, while low humidity can make paper brittle.

For most paper-based materials, the ideal storage conditions are around 65–70°F (18–21°C) and 40–50% relative humidity. These parameters are maintained in modern archives through climate control systems that monitor and adjust conditions continuously. Light exposure, particularly from ultraviolet (UV) rays, is also carefully managed. Documents are stored in dark rooms or boxes, and any necessary lighting is low-intensity and UV-filtered.

Air quality plays another crucial role. Pollutants such as sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and ozone can accelerate chemical reactions that degrade paper and ink. Archives use filtration systems to keep air clean and stable. Together, these environmental controls slow the natural aging process and reduce the risk of catastrophic loss.

Proper Storage Materials

Once a stable environment is ensured, the next consideration is how to physically store the records. Ordinary cardboard boxes and plastic sleeves can introduce acids and other contaminants that hasten deterioration. Instead, archivists use acid-free, lignin-free folders and boxes. These materials are chemically stable and help buffer the documents against environmental fluctuations.

Documents are stored flat whenever possible to prevent folding or creasing. Oversized materials like maps or registers may be stored in flat file drawers or rolled around large, acid-free tubes. For bound volumes, such as parish registers or ledgers, custom book supports or boxes are made to reduce stress on the bindings.

Photographs and negatives, which may accompany genealogical records, require their own specialized enclosures—typically made from inert polyester or polyethylene sleeves that prevent chemical interaction with the image materials.

Digitization: Preservation Through Access

One of the most transformative advances in record preservation over the past few decades has been digitization. Scanning or photographing historical records creates high-resolution digital copies that can be accessed online, reducing the need for physical handling of the originals. This not only preserves the physical documents but also makes them available to a global audience of researchers.

Digitization, however, must be done carefully to prevent damage during scanning. Fragile or tightly bound records may need to be photographed using overhead cameras instead of flatbed scanners. Archivists also follow strict metadata and file format standards to ensure the digital versions remain accessible over time. Common archival formats include TIFF (for images) and PDF/A (for text), chosen for their stability and wide compatibility.

Beyond simple preservation, digitization often includes optical character recognition (OCR) to make the text searchable, greatly enhancing usability for genealogists and historians. Many national archives, libraries, and genealogical organizations have ongoing digitization projects that bring centuries-old records into the digital age.

Preventing Biological Damage: Mold, Pests, and Microorganisms

Biological threats have destroyed countless historical records over the centuries. Mold, insects, and rodents can cause irreparable damage to paper and bindings. Modern archives employ a range of preventive strategies. Relative humidity is kept below 50% to discourage mold, while regular inspections and good housekeeping practices prevent insect infestations.

When pests are detected, non-chemical treatments are preferred. Freezing is one common method—documents are sealed in airtight bags and frozen for several days to kill insects and larvae without introducing harmful residues. For mold, the affected materials are dried, vacuumed with HEPA filters, and treated in specialized chambers that remove spores safely.

Disaster Preparedness and Recovery

No preservation plan is complete without a disaster management strategy. Floods, fires, and other natural or human-made disasters can destroy centuries of history in moments. Archives therefore maintain disaster preparedness plans that outline procedures for prevention, rapid response, and recovery.

Fire suppression systems use inert gas rather than water, which could cause further damage. In the event of flooding, wet documents are quickly frozen to halt deterioration until they can be safely air-dried or freeze-dried later. Staff members are trained in emergency recovery methods, and regular drills help ensure readiness. Redundant storage—keeping copies of vital records in separate geographic locations—adds an additional layer of protection.

Microfilming: The Precursor to Digital Preservation

Before digitization became widespread, microfilming was the primary method for preserving and distributing old records. Microfilm involves photographing documents at a reduced scale onto reels of film that can last for hundreds of years when stored properly. Many vital records from the 19th and 20th centuries exist today because they were microfilmed by libraries, archives, or organizations such as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which maintains one of the world’s largest collections of genealogical microfilms.

Even today, microfilm remains a trusted preservation medium because it’s stable, requires no special technology to read (just light and magnification), and is resistant to data corruption that can affect digital files. Many institutions continue to use both digital and microfilm copies for redundancy.

Handling and Access Policies

Even the most carefully preserved document can be damaged through careless handling. For this reason, archives have strict access and handling protocols. Researchers may be required to use gloves or wash hands before handling materials. Pens are often prohibited in reading rooms to prevent accidental ink marks. Documents are supported with foam cradles or weights to avoid stress on bindings.

High-resolution digital or microfilm copies are often provided for public use, reserving the originals for only the most essential cases. This careful balance between access and preservation ensures that historical records can continue to educate and inspire without being compromised.

The Role of Technology and Artificial Intelligence

Emerging technologies are opening new possibilities for record preservation. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning tools can now analyze faded handwriting, reconstruct missing text, or identify patterns in large archival datasets. Spectral imaging allows conservators to reveal writing that has faded or been erased, capturing wavelengths invisible to the naked eye.

3D scanning and digital modeling are also being used for complex materials, such as seals, embossed covers, or scrolls that can’t be unrolled safely. These technologies don’t replace traditional conservation work but complement it, providing powerful tools for preservation and study.

Institutional and Global Cooperation

Preservation of historical records is not confined to one country or institution. It’s a global effort involving cooperation among national archives, libraries, universities, religious institutions, and private collectors. International organizations such as UNESCO, the International Council on Archives (ICA), and the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA) promote standards and training programs to ensure best practices worldwide.

Many institutions also collaborate through shared databases and digitization projects. For example, partnerships between the National Archives, FamilySearch, and Ancestry.com have made millions of birth, marriage, and death records freely accessible online—while ensuring that the physical originals remain safely stored.

Ethical and Legal Considerations

Preserving historical records also involves ethical decisions. Who owns the records? How should they be shared? Sensitive documents—such as adoption records or medical reports—may require restricted access to protect privacy. Archivists must balance the right to information with ethical stewardship, ensuring records are handled respectfully, especially those tied to marginalized or indigenous communities.

Legal frameworks such as copyright law and data protection regulations also influence how records are digitized and distributed. Proper documentation and adherence to archival ethics help maintain trust between institutions and the public.

The Continuing Mission of Preservation

Ultimately, the preservation of historical records is a commitment to the future. Each birth certificate, death record, or family ledger represents a fragment of the human story. Without preservation efforts, those fragments would vanish—taking with them the evidence of lives lived, families formed, and societies built.

Today’s archivists act as custodians not only of paper but of memory itself. Through their careful attention to materials, environments, and technologies, they ensure that the past remains tangible, readable, and meaningful to generations yet to come. Every stable temperature reading, every encapsulated document, and every scanned image is part of a quiet but monumental mission: safeguarding humanity’s shared history.

Conclusion

Preserving old historical records such as birth and death certificates requires a multifaceted approach that blends scientific precision, technological innovation, and deep respect for the past. From cleaning and repair to climate control, digitization, and ethical stewardship, every step contributes to the longevity of documents that may be hundreds of years old. As technology advances, new tools will continue to enhance preservation, but the fundamental goal remains unchanged—to protect the fragile traces of our collective story so that future generations can trace their roots, understand their heritage, and learn from the enduring record of human experience.